On Thursday evening (VE Day) the Scouts learnt about the invaluable contributions of Scouts during both World War I and World War II.

Scouting, founded in 1907, was still in its infancy when the First World War broke out, but its members quickly proved their worth in supporting the war effort. By the time of the Second World War, Scouts had become an integral part of community resilience, assisting in various ways both at home and abroad.

Scouting in the First World War

During World War I, Scouts played a crucial role in supporting their communities. Their training in signalling, first aid, and navigation made them ideal for tasks such as:

- Carrying messages between military units and local authorities.

- Assisting with air raid precautions and fire-watching.

- Helping farmers with agricultural work to support food production.

- Guarding railway lines and telegraph stations to prevent sabotage.

Scouts could earn badges that reflected these wartime responsibilities, such as:

- Signaller Badge – for proficiency in Morse code and semaphore.

- First Aid Badge – for demonstrating medical knowledge and emergency response skills.

- Pathfinder Badge – for navigation and map-reading expertise.

Scouting in the Second World War

By the time World War II began, Scouts had already established themselves as a reliable force for community support. Their wartime tasks included:

- Helping evacuees settle into new homes and providing comfort to displaced families.

- Delivering messages during the Blitz when telephone lines were down.

- Assisting in rationing efforts by helping distribute food and supplies.

- Supporting the Home Guard with logistical tasks.

Badges earned during this period reflected their wartime contributions:

- Air Raid Precautions Badge – for knowledge of blackout procedures and bomb shelter safety.

- Messenger Badge – for delivering vital communications under difficult conditions.

- Rescue Badge – for assisting in emergency situations and disaster relief.

Why Scouts Were So Important

The Scouts’ motto, “Be Prepared,” was never more relevant than during wartime. Their training equipped them with practical skills that directly benefited their communities. Many young Scouts later joined the armed forces, carrying their scouting experiences into military service.

Even in prisoner-of-war camps, Scouts secretly continued their activities, maintaining morale and a sense of unity among fellow prisoners. Their resilience and dedication exemplified the spirit of Scouting, proving that even in the darkest times, young people could make a difference.

Remembering Their Legacy

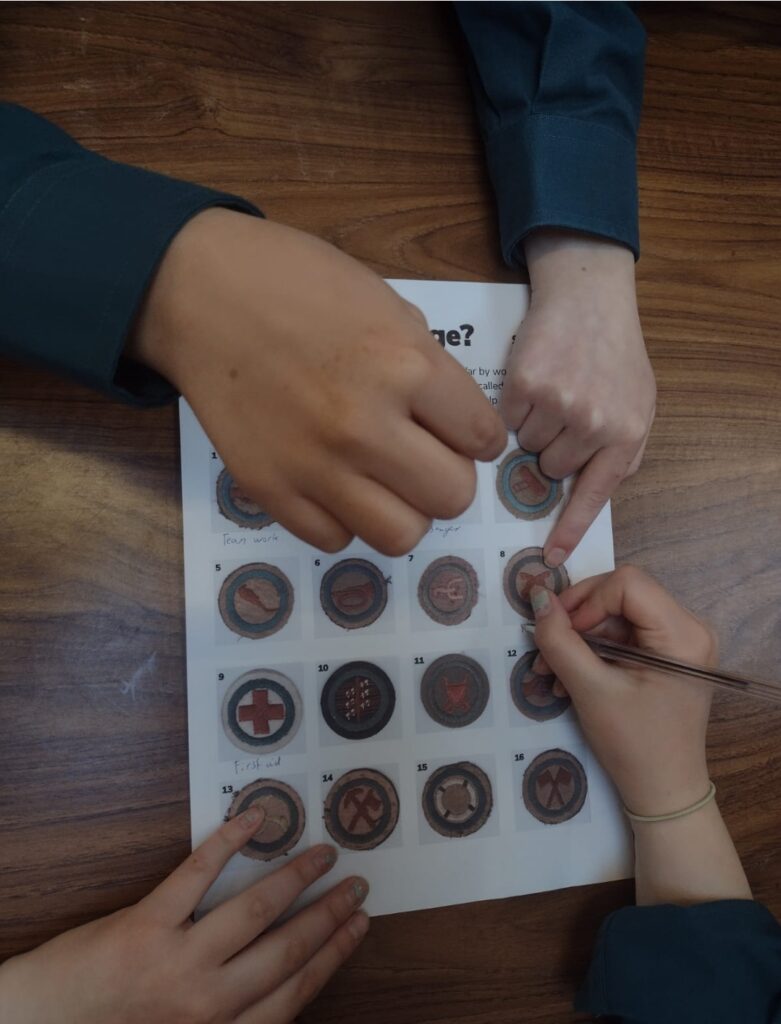

The Scouts did some badge quizes trying to idenitfy the badges that could be earnt in both the first and second world wars. Also the tasks that needed to be learnt for each badge.

Sea Scout rescue

The scouts also learnt how Sea Scouts were involved with Operation Dynamo.

Between 26 May and 4 June 1940, around 340,000 members of the British Army and their French and Belgian allies were evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk on the coast of France.

Officially known as Operation Dynamo, the rescue mission saw hundreds of civilian owned boats pressed into service. They crossed the channel to help those stranded on the shore.

The operation has been immortalised in numerous films, including Darkest Hour (2017), Their Finest (2016), Dunkirk (1958, 2017) and Atonement (2007).

Despite such fame few people realise that Sea Scouts played their part among ‘the little ships of Dunkirk’.

The following extract was written for The Scouter, a predecessor to the later Scouting Magazine, in July 1940.

It was written by the Group Scout Leader of the Mortlake Sea Scout Group, who crewed the 45ft motor picket boat, ‘Minotaur’, during Operation Dynamo.

The Scout Leader is believed to be Mr Tom Towndrow. He received Admiralty orders on the night of 29 May to sail the Minotaur to a staging area in the Thames Estuary. There they waited on further instructions by the Royal Navy.

‘By midnight the Crew was found and, at 8.30am, we were underway down river, refuelling and taking on stores and water as we went. At 8pm, we reported to our destination and were given further instructions to proceed to a south-east port. We made it at 9am the next morning.

At Ramsgate, two Naval ratings joined the Minotaur crew and assisted with the loading of fuel and provisions. They all received detailed operational instructions on the morning of 31 May, before making the crossing to Dunkirk, and would have had little knowledge of what they would encounter.

By 10.45 am, we were on our way. The crossing took five-and-a-half to six hours, and was by no means uneventful. Destroyer after destroyer raced past, almost cutting the water from beneath us, and threatening to overturn us with their wash. We approached the beach with great caution at Dunkirk, because of the wrecks. We found things fairly quiet, and got on with our allocated job of towing small open ships’ boats, laden with soldiers, to troop transports anchored in deep water, or of loading our ship from the open boats and proceeding out to the transports.

Conditions didn’t remain quiet for long. We were working about a quarter of a mile away from six destroyers. Suddenly, all their anti-aircraft guns opened fire. At the same time, we heard the roar of 25 German planes overhead. Their objective was the crowded beach and the destroyers. A succession of bombs were dropped. Adding to the deafening noise were air raid sirens sounding continuously on the shore. One ‘plane made persistent circles round us. Another German plane was brought down in flames, far too close for our liking!

After the raiders had passed, we shakily got on with the job. Eventually, our fuel ran low and the engine made ominous noises, so we were relieved from our duty. We took a final load to a trawler, returned to our East Coast base, re-fuelled and turned in for a few hours’ sleep. We were then told to stand by, as fast boats were making the next crossing.

We shipped aboard another motorboat as crew. We left before it got dark, under convoy of a large sea-going tug. Our job this time was to work from the mole at Dunkirk Harbour in conjunction with the tug. The operation was supposed to be carried out under cover of darkness, but with the petrol and oil tanks on fire it might have been daytime. Having loaded the tug, we came away barely in time. As we left the mole, the Germans got its range and a shell demolished the end of it.

On the way back, we Scouts transferred to a Naval cutter that was making the return journey and full of troops. The officer in charge had lost his charts. Knowing the course back, we were able to take over. After a nine-hours’ crossing, we made our East Coast base once more. German aircraft constantly followed all small boats out to sea, gunning the crews and troops on board. Three more members of our Sea Scout Troop crewed other boats from Chiswick that were short of men.’